Similarly, we intuitively relate centrality and importance, says Global Citizen. These distortions of size - if unchecked - can affect our perception of places, says CNN. Alaska looks much more significant than the rest of the U.S. We psychologically prefer larger stimuli and, to larger stimuli, we attribute greater significance. We intuitively relate size and significance. However, the map is incredibly helpful for understanding two common biases in maps: size and centrality. is minimally helpful for navigating the continental U.S. This map available: #alaskahistory /jJU5A2un0N- David Reamer October 20, 2020 I've interviewed several people who grew up Outside thinking AK was SW of CA because of how it's often inset in maps. Map of the United States from an Alaska perspective. Sometimes biases in maps are easy to recognize - like this U.S. In his research with the History of Cartography Project, Edney, a cartographic history professor, said he learned “to ask why maps (were) made, and what cultural, social and instrumental value they have.” For example, if a cartographer finds a country more important, they could place it at the center or draw it larger.

#WHY CARTOGRAPHERS GIVE COUNTRIES DIFFERENT SHAPES HOW TO#

Mapping requires cartographers to decide how to present the world, leading to biased maps.

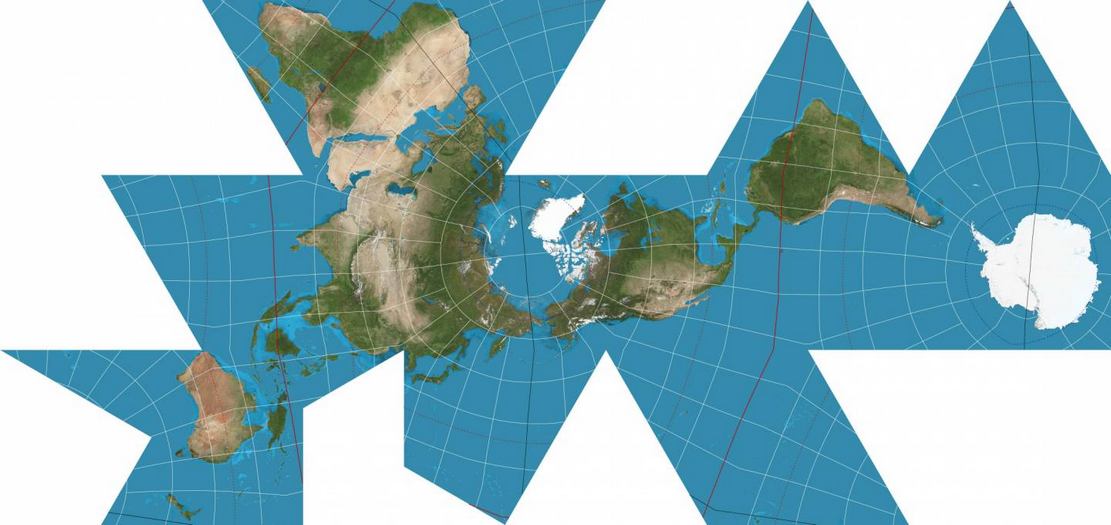

Maps are inherently prone to mistakes because they take three-dimensional space and present it two-dimensionally. This phenomenon is known as “ map bias.” What is ‘map bias’ and why does it matter? The way places are presented on a map affects our perception of those places themselves, reports the Borgen Project. Misrepresentations like these have broader, concerning implications. Africa is bigger than the U.S., Canada, and China put together. Similarly, North America appears much larger than Africa when the opposite is true. On Mercator’s map, Greenland and South America appear nearly the same size, but South America is actually eight times larger. Mercator’s map distorts the actual size of landmasses, overinflating those near the North and South poles, reports National Geographic. “People tend to take maps at face value,” Matthew Edney, a professor and researcher of cartographic history at the University of Southern Maine and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, explained to the Deseret News. However, just because the Mercator map is popular does not mean it's fully accurate. The same method Mercator used continues today and underpins even Google Maps, CNN reported. Mercator’s map showed longitude and latitude lines at 90-degree angles - the first to do so - and helped sailors improve navigation. Developed by Gerardus Mercator in 1569, the map revolutionized cartography with a simple idea: wrap a piece of paper around a globe, imagine the landmasses projected onto the paper and then draw them, Vox explains. In the U.S., the most common and popular map decorating classroom walls is the Mercator Projection Map, per National Geographic. With such significant implications, we must consider: What are our maps showing us about the world around us? Do we agree with what they show? The common map you see “Despite their seemingly mundane nature, maps are contentious, often disputed documents that affect daily life in tangible ways,” writes anthropology professor Sarah Kurnick in her recent paper on Mayan maps published in the journal Maya Anthropological Archaeology. This impacts our understanding of the significance, authority, and stability of the places around us. Maps can size landmasses inaccurately, orient hemispheres arbitrarily or show boundaries statically. While maps are undeniably useful for showing the world around us, they are undeniably biased since cartography is as “subjective as any other artistic endeavor,” writes art historian Nicole De Armandi. Lines on a map often take political stances and carry social implications both for those living at the locale and for those looking at the map.

Twitter showed a map of India with the contested region of Kashmir as a separate country and India is not happy, according to The Guardian. That’s exactly why India is suing Twitter for treason.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)